Okami is a game released in 2006 for Playstation 2,3, and Wii. The gameplay is centred around the white wolf Amaterasu (the Shinto god of the Sun and universe) and her quest to defeat the great evil from a century past, Orochi. Set in the classical era of Japan Okami features a cel-shaded art style heavily influenced by traditional sumi-e (ink and wash painting) techniques. As Amaterasu, the player is given control of the “Celestial Brush”, the use of which is required to traverse environments, defeat enemies and complete quests. Within the game, when players hold down a button, the screen freezes and changes colour to mimic parchment and the player can paint with the celestial brush using the right analogue stick (or Wii motion controls). Depending on context and the shape drawn, the celestial brush can restore life to flora, conjure bombs out of thin air, conduct lightning and slow down time, among other things. The in game menus also feature traditional sumi-e works including many of the characters and items in the game.

Example of sumi-e

Scene from Okami

I found this mechanic fascinating in both a gameplay sense (it is incredibly satisfying to have the world change according to your brushstrokes) and a game design sense, the way both the game aesthetic and mechanic are based heavily on this ancient medium and integrated so well into a modern art form such as Okami.

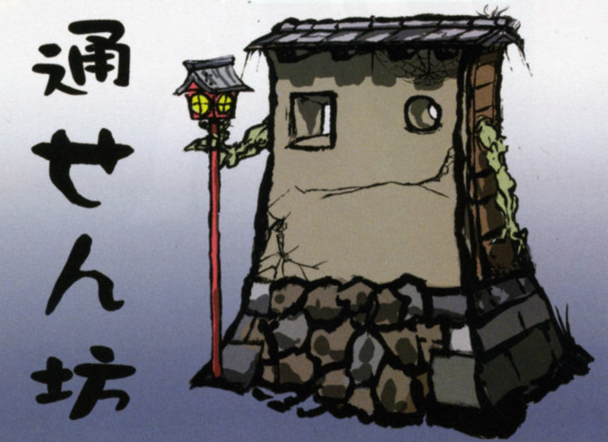

Even the philosophical roots and technical limitations of Sumi-e shape the gameplay processes in Okami. Within the game, usage of the celestial brush is governed by the availability of celestial ink pots, which are consumed by performing an action with the celestial brush. When all of Amaterasu’s ink is depleted, the agency of the player (or artist in this sense) is severely diminished, in the form of loss of ability to use the celestial brush or weapons. This link between ink and facility bears obvious ties to visual art techniques, but the similarities don’t end there. Because of the nature of the medium and the tools involved (black water based ink of various dilutions and light coloured paper) a misplaced stroke is an unfixable error. In accordance with this, artists new to the medium spend much time practicing their handling of the brush and inks. Okami reflects these conditions in the form of ingame punishments for poorly wielding the celestial brush, inflicting penalties like the removal of ink from your store or forcing the repetition of a gameplay sequence. At certain points throughout the game, the player is faced with an enemy called ”Blockhead”, and he is one of the main reasons for this blog post. As Kevin has mentioned previously, this character appears,blocking your path to where you must go, and you must defeat him to progress. Unfortunately in order to defeat him, you must come to terms with and complete an entirely new and very difficult minigame. The minigame involves small beacons (highlighting structural weakness) appearing on Blockhead’s body and then disappearing, the objective of the player being to remember the precise locations of the beacons and use the celestial brush to paint points where they previously were. In so doing the player defeats Blockhead and is able to progress within the game. The catch is that Blockhead is an incredibly well put together chap and thus will not be defeated unless you hit the exact locations, within a time limit. While this may seem like an unfair jump in difficulty, it shows great parallels to sumi-e painting in its unforgiving need for precision, concentration and practice.

The goal of ink and wash painting is to capture the essence of a subject rather than to render its image,and Okami goes a fair way to instilling the essence of sumi-e into videogame form. While it places restrictions on what shapes will have an effect in game, the player may draw whatever they please (as long as ink remains) on their canvas. In this way Okami becomes both a platform for art as well as an example of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.